When Laughter Became a Crisis: The Tanganyika Epidemic of 1962

By Angelica Praxides · Published

Angelica is a book lover who thrives in quiet libraries, enjoys good coffee, and chases something new to learn every day.

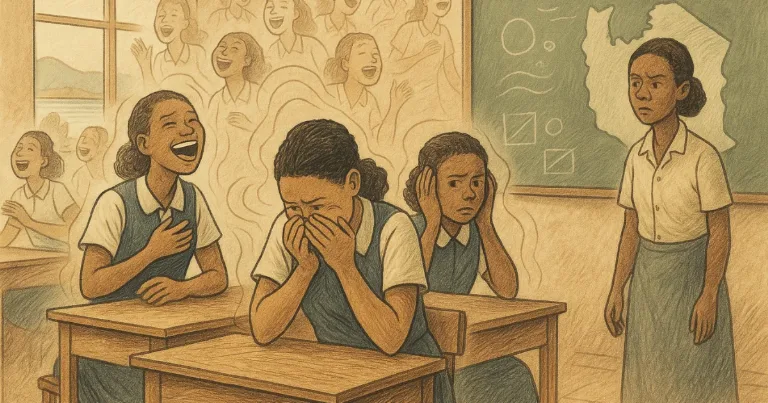

In early 1962, at a small girls’ boarding school near Lake Victoria, a teacher watched one of her students break into laughter. At first it looked like a normal giggle during class. Then it went on for minutes, then longer, until the girl could not stop. Soon, two friends joined in. None of them could explain why.

Within weeks, that strange laughter had spread through dormitories, classrooms, and nearby villages. Schools closed, doctors arrived, and a local puzzle turned into a regional crisis. What began with three girls in Kashasha became one of the most famous examples of a shared illness with no clear germ behind it.

How Uncontrollable Laughter Took Over Kashasha

The outbreak started on 30 January 1962 at a mission-run boarding school for girls in Kashasha, in what is now Tanzania. The school had 159 pupils, mostly teenagers. Medical reports from the time describe three students who suddenly developed fits of laughter they could not control. The episodes came in waves, often with restlessness, crying, and trouble concentrating.

The laughter did not stay with those three girls. Over the following weeks, around 95 of the 159 pupils experienced similar episodes. Teachers and staff were mostly unaffected, which already made the pattern unusual. Some girls had short bursts that left them tired but able to continue. Others had repeated attacks over days, even up to two weeks, and were left exhausted and shaky.

Lessons fell apart. A class could be calm one moment, then a string of giggles would run across the room like a spark. A girl trying to keep a straight face would hear another student start, feel her own chest tighten, and then lose control as well. It was impossible to run a normal timetable when students might burst into laughter or tears without warning.

By 18 March 1962, the school could no longer function and was closed. The decision made sense in the moment, but it had an unexpected effect. When the girls went back to their home villages, some brought their symptoms with them. Others carried only the memory and fear of what they had seen.

Over the next months, similar episodes appeared in nearby communities. In the village of Nshamba, dozens of people began to experience laughing fits, crying, and agitation. A girls’ middle school at Ramashenye reported its own cluster of students with the same strange behaviour. In total, reports from the period suggest that around a thousand people were affected in the wider Bukoba district, and around fourteen schools closed at least once.

The word "laughter" can sound light, but the symptoms were not. Doctors noted fainting, chest pain, shortness of breath, rashes, and anxiety mixed in with the laughing attacks. Families were scared, not amused. They did not see a joke. They saw children who could not control their own bodies.

Then, very slowly, the wave faded. Over roughly a year and a half, new cases became rarer. There was no single cure, no vaccine, and no obvious environmental change to point to as the turning point. The epidemic simply burned out.

Why Doctors Now See It as a Shared Stress Reaction

At the time, people searched for a simple cause. Was there a virus, a chemical, or a poison in the food? Investigators looked for toxins and infections but did not find a clear physical trigger that could explain all of the cases.

Later, as researchers compared the Tanganyika episode with other cluster events, a different explanation became more convincing. Most now place it in the category of mass psychogenic illness, sometimes called epidemic hysteria. In this kind of outbreak, real symptoms spread through a group, but the main fuel is shared stress and expectation rather than a germ.

The background to 1962 helps that picture make sense. Tanganyika had only just gained independence in 1961, and the whole country was in a period of rapid change. Students at mission schools were under pressure to succeed academically, often carrying hopes for their families’ future. At the same time, they were away from home, navigating strict rules, new cultural expectations, and uncertain job prospects.

These conditions are similar to other documented outbreaks of mass psychogenic illness. Symptoms appeared mainly in adolescents and young adults, people who are especially sensitive to social cues and group mood. The pattern followed social lines rather than simple physical contact. It moved along friendships, families, and school networks, not through casual meetings in markets or workplaces. When one school closed, the problem moved rather than stopping instantly.

Crucially, none of this means the people involved were pretending. The fear, shortness of breath, and loss of control described in reports from the time were real. In mass psychogenic illness, the brain and body respond to stress in ways that feel physical. Heart rate, breathing, muscle tension, and even laughter can all be pulled into the same loop.

Seen this way, the Tanganyika laughter epidemic becomes part of a longer pattern of shared breakdowns. Historians often mention it alongside a sixteenth century dancing outbreak in Strasbourg, where crowds were described as moving until collapse. The behaviour in each case looks different, but both sit in the same family of events where communities under pressure develop dramatic, contagious symptoms.

The details also feel familiar if you picture them in a modern setting. A few students in one building begin to act strangely. Their classmates watch and feel a mix of fear and curiosity. Rumours move faster than official explanations. Parents hear only that "something" is happening at school and react with worry. Each new case makes everyone more certain that a hidden danger is at work.

Today, doctors and historians look back at the Tanganyika laughter epidemic as a reminder that illness is not only about microbes. It is also about the stories people share, the stress they carry, and the social worlds they move through. Under the right kind of pressure, a community’s nervous system can start to echo itself, until laughter turns into a crisis and a single classroom becomes the centre of an epidemic no one can fully see.